At a basic level, the answer to this question relates to whether one is taxed at a higher marginal tax rate now compared to when one will be withdrawing these dollars in retirement. If one's marginal tax rate is higher now than in retirement, it is beneficial to contribute to the traditional IRA or 401(k), taking the tax break now, in order to pay lower taxes later in life.

However, if the marginal tax rate will be higher in retirement, go ahead and contribute to the Roth account now in order to avoid higher taxes later in life.

By this standard, many young people at the start of their career will have lower salaries and be in lower tax brackets relative to later in life and will benefit from contributing to a Roth. Mid-career individuals at peak earnings will be in higher marginal tax brackets and may see more advantage from a traditional tax-deferred approach.

"Roth IRAs: More Effective (and Popular) Than You Thought"

This isn't the full story, as a controversial study from T Rowe Price pointed out. Their conclusion was that "most investors should use Roth IRAs over Traditional IRAs." They make this case even if marginal tax rates will be lower in retirement. The argument relates to their table on the first page of their study, which considers an individual who saves $1000 in a Roth IRA vs. saving $1000 in a traditional IRA and another $250 in a taxable account. That additional savings is the result of the $250 in reduced taxes created by making a contribution to the traditional IRA when someone is in the 25% tax bracket. Their point is that taxes will have to be paid over time from the taxable account, reducing the power from tax deferral, and that this gives a much greater edge to the Roth.

This point is valid, but I think they've really overstated the impact this point has on the final decision. I haven't been able to exactly replicate their study, because they are not clear about some of their assumptions, and because I think they have a really odd way to generate retirement income that results in a rapidly growing spending path over retirement. To replicate their study the best I can with what I think are more reasonable retirement spending assumptions, I assume the following:

Roth IRA: Invest $1000 per year until age 65, which grows at 7%. Then for each year of a 30-year retirement, spend a fixed amount each year so that the account balance falls to $0 in year 30, assuming a 6% return. [with a fixed 6% return and withdrawals taken at the start of the year, the sustainable withdrawal rate for 30 years is 6.85%]

Traditional IRA: Invest $1000 per year until age 65, which grows at 7%. Then for each year of a 30-year retirement, spend a fixed amount each year so that the account balance falls to $0 in year 30, assuming a 6% return. The post-retirement tax rate is applied to these withdrawals, reducing the spendable income accordingly. (RMDs are not considered)

Taxable Account: Invest $250 per year until age 65, which grows at (1-.25)*7% = 5.25%. Then for each year of a 30-year retirement, spend a fixed amount each year so that the account balance falls to $0 in year 30, assuming a (1- retirement tax rate)*6% return.

In all cases, I assume new contributions are added at the end of the year, and withdrawals are taken at the start of the year.

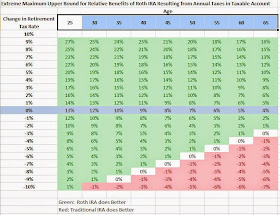

With these assumptions, I created the following version of their table:

Now, as I note in the table, these are still extreme upper bounds about the relative benefits of the Roth IRA created by the tax issue for the taxable account. Why?

First, the assumed returns are rather high. Based on the fact that someone is saving $1000 every year over a potentially long-career, we've got to assume these are compounded real returns, which essentially means that this person is investing in 100% stocks and getting the average historical return (which is about 6.5% since 1926). A more diversified portfolio with a lower stock allocation will lower these returns, and a lower return accordingly reduces the relative benefits of the Roth.

Second, the rather basic assumption about the taxes being applied to the taxable account is not appropriate. It assumes all portfolio growth is taxed each year at the marginal income tax rate. This ignores the fact that capital gains taxes are deferred until when withdrawals are taken, and that long-term capital gains can be taxed at a lower rate. A more realistic assumption about how taxes will affect the taxable account would lower the taxes being paid each year, and therefore reduce the relative benefits of the Roth.

Third, and this is a matter I want to discuss more in a subsequent post, regards if one is making charitable contributions over time. Donor-Advised Funds provide a way to contribute appreciated shares from your taxable account, which then basically let's you reset the cost basis of your account by contributing shares to charity rather than cash, but using that cash to replenish the shares just given away at a new higher cost basis. This reduces the disadvantages of having assets in taxable accounts.

Fourth, the study is completely ignoring the possibility of making Roth conversions at low marginal tax rates in years when income is low. This is a way to get the tax rate paid on those dollars to be much lower than otherwise, making it realistic to assume lower "post-retirement" tax rates to a degree that could make the traditional IRA look quite attractive.

Other Factors Which Favor Roth Accounts

- Roth accounts do have extra flexibility in retirement, since withdrawals do not show up on tax forms. By using Roth distributions strategically, it could help to avoid paying taxes on Social Security income, capital gains, Medicare premiums, etc., in retirement.

- Roth accounts are not impacted by RMDs. With tax-deferred accounts, RMDs will give you less control about when you have to pay taxes, and these RMDs could result in higher taxes on other income sources as they push up your AGI.

- If the government raises tax rates in the future, this would benefit those who have already paid their taxes in advance with the Roth.

Other Factors Which Favor Tax-Deferred Accounts

- The potential value from making Roth conversions cannot be overlooked. Suppose you retire at 62 and delay taking Social Security to 70. This provides 8 years to get extreme about moving lots of assets from a tax-deferred account to a Roth account at 10% or 15% marginal tax rates.

- Retirees who are not extremely wealthy will probably be in a lower tax bracket once they stop working. This favors the tax-deferred approach.

- Some folks distrust the government to the point that they seek to take any tax breaks when they can, as who knows what tax changes will happen in the future. Some of the benefits of Roths (such as not having RMDs or not being counted in the provisional income which determines whether Social Security benefits are taxed) could be eliminated one day. Of course, this sort of distrust could extend to an assumption that taxes will be higher in the future, which leans toward a Roth.

Conclusions

When I first read the T Rowe Price study, it got me really thinking about whether I may be making a mistake about how I'm managing my divisions between tax-deferred and Roth accounts. But in the end, I think I'm making the right decision. Tax diversification is important, and so it is good to have some funds in tax-deferred accounts and some in Roth accounts. I don't think there is a strong reason to shift completely over to the Roth account, to the extent it is even possible. Nonetheless, as my career progresses I will keep this issue in mind more, as there may be a point where a bigger allocation to Roths could make sense.

A good analysis and explanation of all of the various qualifications. There is one qualification that seems should be quantified:

ReplyDelete"Second, the rather basic assumption about the taxes being applied to the taxable account is not appropriate. It assumes all portfolio growth is taxed each year at the marginal income tax rate. This ignores the fact that capital gains taxes are deferred until when withdrawals are taken, and that long-term capital gains can be taxed at a lower rate. A more realistic assumption about how taxes will affect the taxable account would lower the taxes being paid each year, and therefore reduce the relative benefits of the Roth."

In your example, the 250 would be put into, say, VTSMX for the entire period of accumulation and withdrawal. The tax on invested amounts would only apply to fund distributions which historically are probably closer to 1.5 - 2% than 7% (and some capital gain). A portion of the withdrawals would be taxable capital gains, highest basis first. Not too difficult to come up with effective tax rates, maybe around 5 -10% of distributions.

It seems that this would be a fairly simple fix and would give a more realistic result.

John,

DeleteThank you. Good suggestions. It also shouldn't be too hard to develop a way to just keep track of the cost basis and then pay taxes accordingly on the capital gains.

Wade - your comments about contributing to a donor advised fund are spot on. I live in California, with high state taxes. My regular tax bracket is the same working and in retirement, but I'm subject to AMT "at the margin" while working; don't expect to be in retirement. As a result, my de facto marginal tax rate while working is 9-11% higher than it will be in retirement. Each year, I gift enough highly appreciated shares to my donor advised fund to eliminate my AMT exposure. This is a very effective way for me to leverage the tax code to maximize the effectiveness of my charitable giving.

ReplyDeletePhil,

DeleteGreat, thanks for sharing about a more complex case where the donor-advised fund can help. I don't even pretend to know about tax planning for the AMT.

The model used here compares apples with oranges. The benefits of these accounts accrue to (are caused by) only those dollars that are put in the accounts. Any $$ invested outside is irrelevant. To compare apple with apples you start with equal $x gross wages. Since no taxes are paid on the wages when contributing to a TradIRA that account will be funded with a larger contribution than a RothIRA.

ReplyDeleteE.g. at 25% tax rate and $1,000 gross wages, a Trad contribution will be the full un-taxed $1,000. Only $750 after-tax will be available to fund a Roth.

Whether you get the benefit of the Trad's tax reduction via (a) a refund, or (b) a reduction in taxes otherwise owing at year end, or (c) as higher paycheques during the year (if US employers are allowed to reduce tax with-holdings as Cdn employers are) makes no difference. Every contribution comes with the value of the tax reduction. How you realize that value is your personal decision. It does not impact the relative benefits of the accounts.

This proper analysis is distorted by American limits to maximum contributions that set the same $x for both types of accounts. These limits impact those making the maximum contributions because $x in a Roth is worth more than $x in a Trad. But this is an implementation problem. It does not impact the relative benefits of the two accounts.

The tax rates to be used in any analysis must be the 'effective tax rate' not the statutory rates. The effective rate is impacted by the delay in realizing capital gains, by the preferential rates applied to certain types of income and the combination of income-types for each asset, tax with-holdings lost on foreign income, your tax bracket, etc

The $benefits from sheltered profits of both Roth and Trad accounts are exactly equal, It equal the difference between the future value of the after-tax savings after whatever time frame you like, compounded at the nominal rate of return vs. compounded at the after-tax rate of return.

A Trad has another possible bonus or penalty equal to the $withdrawn multiplied by the difference in tax rates between contribution the withdrawal.

Thank you for the feedback.

DeleteI'm not seeing how this is an apples and oranges comparison. I do think that the T Rowe Price study got this part of it right.

Suppose we're at the end of the year and after covering tax bills and household expenses, you still have an extra $1000 that you'd like to save in either tax-deferred or tax-free.

With tax-free, you put the $1000 into the account and never have to pay taxes on it again.

With tax-deferred, you can put the full $1000 into the account. But you don't really own all of it as the government has a claim on a share of this, which will be determined by the marginal tax rate when it is withdrawn. At the same time, your current tax bill also gets lowered by $250. But you had better save that $250 (in a taxable account) as a way to fund those future tax payments.

I've been getting a lot of emails about this too. And I do think there is some confusion, though not necessarily with your case.

The more typical way to compare would be to consider $750 in a Roth vs. $1000 in tax-deferred.

The T Rowe Price Study sets it up in a slightly different way, but one which is still an equally fair comparison:

$1000 in a Roth vs. $1000 in tax-deferred + the tax savings in a taxable account.

Or to put another way, yes it is true that you can technically shelter more in a Roth since the government doesn't have a claim on any of those assets. But to make a fair comparison, you also should invest the tax savings that accompany the tax-deferred contribution in order to one day pay those taxes. This gets us back to the point about deciding with regard to whether taxes at the margin will be higher or lower when withdrawals are made, but with the added point that you also have to make a proper consideration about taxes on the tax savings kept in a taxable account.

Just one more follow-up about this. The:

Delete$1000 in a Roth vs. $1000 in tax-deferred + the tax savings in a taxable account

is the way I personally would be thinking about this.

There is a behavioral mistake which could be made though and that is simply to compare

$1000 in a Roth vs. $1000 in tax-deferred

with those tax savings being used to purchase some extra goods and services. In this case, investing in the Roth means saving much more than otherwise, since the government doesn't have any claim on a share of these assets. As a mental accounting trick to save more, the Roth would be preferable in this case.

Those replies did not address the two arguments I made for 'why' your model is not correct.

Delete(1) The benefits of these accounts accrue to (are caused by) only those dollars that are put in the accounts. Any $$ invested outside is irrelevant.

(2) Whether you get the benefit of the Trad's tax reduction ....

(a) via a refund to be invested in a taxable account, or

(b) via a refund to be added to the original Trad's contribution, or

(c) via a refund to repay a loan taken out to gross up the original contribution, or

(d) by a reduction in taxes otherwise owing at year end, or

(e) as higher paycheques during the year (if US employers are allowed to reduce tax with-holdings as Cdn employers are)

makes no difference.

Every contribution comes with the value of the tax reduction. How you realize that value is your personal decision. It is not the fault of the IRA if someone delays claiming the refund, or fritters away the refund on a vacation, etc. Those are all just personal choices.

Any model of the IRA must apply to everyone, no matter how they choose to realize the contribution's tax reduction. The only way to do that is to compare equal gross wages ... resulting in a TradIRA 's contribution being larger than the Roth's contribution.

The replies above talk about 'fairness' in the comparison of Roth's to Trad's. It is not fair to compare (as this article does)

Delete(a) a model where all the saving are put in a tax-shelter, vs

(b) a model when the savings are split between a tax-shelter and a taxable account.

Of course (a) comes out ahead. It is pre-ordained by the unfair comparison.

The justification of that comparison because ..." to make a fair comparison, you also should invest the tax savings that accompany the tax-deferred contribution in order to one day pay those taxes" misrepresents the model I am arguing, where all the TradIRA's tax savings ARE considered invested --- inside the TradIRA - regardless of the individual's choice of cash flows.

May I suggest you watch the 2nd video of the series linked from my post's name. The Canadian RRSP = TradIRA, and the TFSA = Roth. https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCYf70uCj5q4GRWYC0wVtdxg

I'm not sure why we are having a disagreement.

DeletePerhaps we are focusing on slightly different questions.

Your question may be more along the lines of which kind of account is inherently superior?

But my question is: How can someone invest a fixed amount of money today to get the most post-tax spending power in retirement. That's why it's relevant for me to say that they are going to invest today's tax savings as well. If they don't, then Roth does better. But that's not an interesting question to me.

Test post. I am an AICPA member and am very passionate about this topic. I'll choose to make only a simple point. Since the 2013 Tax Relief Act we now have a much more complicated Individual Tax structure that gets very aggressive for high income earners. (Michael Kitces has a nice summary chart on his site. Robert Keebler has some incredible intellectual capital on his site too.) Simple Point - Many incredible resources expect the US Individual Tax code may (BAB thinks will become!) become more aggressive. I personally believe there is short term and long term benefit to at least pool some material portions of 'your' current taxable income toward ROTH IRA's vs traditional. Consider filling your current Federal Marginal Tax rate (this will also carry a load on the effective rate - but decisions should be made at the margin) to that brim with the Roth contribution vs a traditional. You will enjoy this as added flexibility when and if you ever make it to RMD's. Love your work Wade! Thank you for all these efforts to enlighten our wisdom! Anonymous Poster - Bruce Bohannon

ReplyDeleteThanks Bruce. Will you be at the AICPA-PFP conference in January?

DeleteI can agree with most of this study. It seems to make sense as a good rule of thumb. I take offense more to the closer to retirement and in retirement assumptions and findings.

ReplyDeleteWe do a lot of tax projections as part of our financial planning process and the biggest issue I see in regards to Roth vs Traditional is Social Security (SS) taxation in retirement. Depending on pension income, capital gains, and other sources; the amount of Roth conversion and/or which account to draw from is heavily impacted by SS taxation.

From my current point of view, the ideal situation would look like this. I would like to have a mockup of a standard tax projection entering retirement 10 years before SS is drawn to see the best way to maximize the tax code. This mockup would show which choice is better in the Roth vs Traditional battle.

For most of middle income America, the best choice between Roth and traditional is based on how much of Social Security taxes will be added to that. If there is some great planning work between when to draw SS, what account to contribute to, and when to convert; then for a lot of clients the best decision will be reached as to having Roth or Traditional dollars. It is sad to see the lack of care to tax planning as financial advisors in something that can be so beneficial to people.

It is my dream that the integration of taxes and investments would be a common practice.

In our CPA firm's tax practice, we have seen a number of cases in which distributions from large traditional IRAs have been used to fund large deductible costs of long-term care. In effect, the IRA distributions have then been tax free, due to the offsetting deduction of the long-term care expenses as medical expenses.

ReplyDeleteWe have also seen situations in which after-tax funds were used to fund long-term care expenses and we have recommended large traditional IRA conversions to Roth IRAs in those years, to make the conversions without incurring an income tax liability.

This has made us less eager to recommend conversions of traditional IRAs to Roth IRAs in clients' younger years. For many years I tried to convince one client in her 70's to convert her traditional IRA to a Roth. She steadfastly declined my advice. Now, in her 90s, her traditional IRA is being used to fund her long-term care expenses with essentially tax-free distributions, due to the deductibility of long-term care costs as medical expenses.

I realize than one, or a few clients, does not constitute a study. But these "true stories" need to be considered by planners in their day-to-day dealings with their clients, and the advice provided to those clients.

Neal and Anonymous,

ReplyDeleteThank you both for sharing. These are great thoughts.

Thanks for sharing such an important article, I highly recommend it. Financial advisors Manchester

ReplyDelete